Born Detroit, MI, 1952/Art studies at Wayne State University, Detroit/Lives in Hazel Park, MI

James Puntigam’s artwork has come a long way since 1986, when he quit his job at the Michigan Department of Social Services, obtained a city vendor’s license, and began making money drawing caricatures in downtown Detroit during events at Hart Plaza and the Eastern Market. Though he might still do the occasional caricature, his main work now is in making linocut prints. His extensive experience over the years has included drawing with graphite on paper, and painting with acrylics on canvas, sheetrock, board, and other surfaces.

Puntigam’s acrylic paintings on slate pieces, for example, are done on discarded slate shingles he found in a field in Detroit. He immediately knew the textured and irregularly shaped objects would make excellent “canvases.” And he liked the continuity: rock born of the ages/hewn by man into practical roof shingles/discarded as part of society’s refuse/turned into art…for the ages!

Puntigam’s later series of sangha (monk) trees recalls influences that sprang from a three-month introduction to the practice of Buddhism undertaken at the Still Point Temple on Trumbull. The pieces started with random lines, drips and splatters from which Puntigam picked out forms—in the beginning trees, that at some point began to incorporate faces. The sangha trees paintings are allowed to happen, the resulting trees and backgrounds made of face-images offering a reminder that man is in nature as nature is in man.

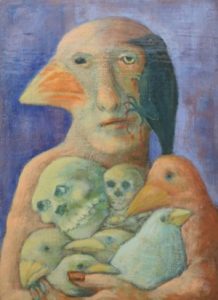

Puntigam on a whim once painted a bird-man, fully clothed in trousers and jacket, in the style of his former teacher and Cass Corridor artist Bradley Jones. The piece readily sold when shown at the legendary gallery and performance space Zeitgeist Gallery, where Puntigam was director from 2001 until it closed in 2008. He went on to create many more “Birdman” pieces, the underlying idea behind them being that to Puntigam, birds represent purity, truth and clear moments. On Top of the World, Ma (2011) shows a recurring theme in the Birdman series in the morphing of one bird creature into another, beaks and eyes often doing double duty for two or more birds. This piece gives a lenticular quality to the three-faced creature. Wonderfully challenging yet inviting.

Puntigam relates that Gathering Memories (2011) can be seen as an evolution of the Birdman shown, his earlier and later selves nestled safely in his lap, and one arm in the process of transformation. The still-live skull depiction looks at something of interest off to the side while a black crow manifestation of the Birdman spurs on the evolution by providing the painful stimulus.

Along with Jones, and the raw art of Sam “Grandpa” Mackey, whom he met and befriended when living in one of the houses on the Heidelberg Project block in the early 1990s, another major influence was teacher Peg Sauer, from whom he learned to draw with emphasis on getting down “the gesture,” wherein the artist summarizes the subject into its most basic components, striving to capture its essence of form and movement as distilled in the starkest of lines (easily said, hardly done). Art Brut exponent Jean Dubuffet also became an influence, as did Jacques Karamanoukian, who ran a gallery in Ann Arbor and helped cement Puntigam’s outsider and expressionist aesthetic.

Puntigam is currently concentrating on linocut prints, using all he has learned over the years about technique, content and seeing—especially as in the fully connected seeing practiced in Zen meditation. He began using his face as a subject, homing in on the minute details as a springboard to fully connect with the subject in all its connectedness to the larger world. He reworks the sketches he likes, such as Tired of the Same Ol’ Okey Doke (2018), for eventual transfer to linoleum. Most importantly to Puntigam, as he tells students in the art classes he teaches at Hannan House: Don’t look at or worry about what you’re drawing; concentrate only on the act of seeing the subject, and the drawing will happen as it will. His portraits fill the range from the charming to the distorted and grotesque (which he finds the more interesting), such as Watching the 11 O’Clock News (2018).

The self-portraits led into his burgeoning “Walker” series of linoprints, the original sketches drawn while people-watching at public places such as the Detroit Zoo. The “walkers” challenge Puntigam to make full use of the quick-sketch gesture method to assess and capture a subject’s mood, physical condition and locus in the moment, in the split second between steps, resulting in drawings of stark honesty that reflect a clarity of mind that comes from decades of practice.

Gary Freeman, November 2018

Copyright Essay’d, 2018